Change your location

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Get HSC Trial exam ready in just a week

Get HSC exam ready in just a week

Select a year to see available courses

Science guides to help you get ahead

Science guides to help you get ahead

In this post, we explain what allegory is, how to analyse it, and how to discuss it in your responses.

Guide Chapters

Join 75,893 students who already have a head start.

"*" indicates required fields

Join 8000+ students each term who already have a head start on their school academic journey.

Welcome to our glossary of Literary Techniques ALLEGORY post. In this post, we provide a comprehensive explanation of what allegory is and how you can analyse it insightfully in your essays. This post expands on one of the many literary techniques that you can find in our Glossary of Literary Techniques for Analysing Written Texts. If you would like to develop your English skills for Years 11 and 12, you should read our Beginner’s Guide to Acing HSC English!

Students commonly ask the following questions about allegory:

In this post, we will give you a detailed explanation of what allegory is.

Allegory is a widely used way of conveying information to audiences. Often composers embed crucial messages or complex ideas inside a narrative. This is used by composers in narratives but also by all of us in day-to-day parlance. Before we look at how to discuss allegory in your Band 6 essays, we need to know how to spot and understand them. So let’s show you how to figure out if something is an allegory and how to unpack what the allegory is trying to convey to you.

1. What is Allegory?

2. How Does Allegory Work?

4. How to Analyse Allegory

5. How to Analyse an Allegory – Step-by-Step

6. Example of Allegory

An allegory is an extended metaphor where objects, characters and events are used to represent abstract ideas or real-world issues.

There are different types of allegory, including social, spiritual, moral or political allegories. Allegories also often reflect the author’s context.

Some texts include allegories (as a literary device), while other texts are allegories. This post will show you how to make this distinction.

Allegory has been a popular storytelling method for centuries. It was especially popular during the Middle Ages, when it was commonly used to turn complex religious and moral lessons.

Many classical myths and religious texts are allegories.

For instance, Spenser’s The Faerie Queene is a rich allegory where knights embody virtues and vices, conveying a moral message through epic narrative.

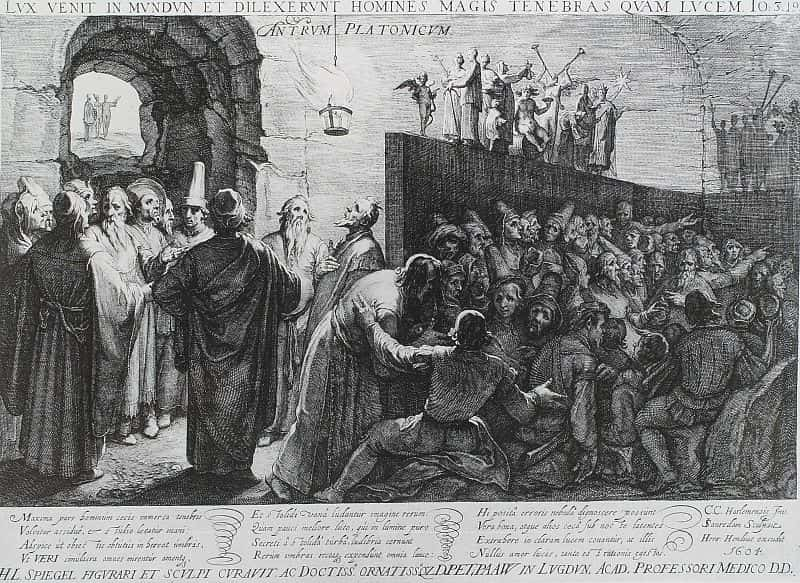

A popular classical allegory is Plato’s Allegory of the Cave.

In this allegory, Plato describes an individual chained up in a cave. Behind them is a wall and a fire, above them, is a raised walkway. All they can see is the wall in front of them where a procession of people and objects are cast in shadow as they walk over the walkway.

One day, this prisoner escapes and she gets to see the outside world and see how different the outside world is from the shadows she’d seen all her life. She returns to the cave to tell her cellmates about this, but they can’t see her, only her distorted shadow and the words seem like strange noises.

You can watch a good animation of this here.

This allegorical figure of the prisoner represents the philosopher—someone who gains insight and understanding, but struggles to explain it to others stuck in conventional thinking.

Plato’s allegory shows how people often cling to familiar beliefs, even when faced with truth. In today’s world of misinformation, “fake news”, and social media bubbles, this idea still feels incredibly relevant.

A well-known contemporary example of an allegorical text is George Orwell’s Animal Farm. In this text, a collection of animals, led by the pigs Old Major, Snowball, and Napoleon take over a farm. As they take control of the property, one of the pigs, Napoleon, becomes more and more authoritarian. Soon his dictatorial rule is no different from the human characters who ran the farm before.

This text is an political allegory of the Soviet revolution of 1918. As the revolution settled in and the USSR developed it became a totalitarian state under the rule of Josef Stalin. In Animal Farm, Napoleon is an allegorical counterpart of Stalin.

Use the free textual analysis planner to develop your study notes and keep track of your possible arguments.

Level up how you analyse texts and take notes with expert strategies and templates!

Fill out your details below to get this resource emailed to you.

"*" indicates required fields

Allegory works in much the same manner as a metaphor, only it is an extended metaphor. If you are unsure of what a metaphor is, read this post on how to analyse metaphors, first.

A metaphor works by comparing two objects. One is the vehicle, the object carrying the meaning, and the other is the tenor, the object that is described. Consider this flowchart as a visualisation of the metaphor process:

An allegory uses the narrative as the vehicle that carries the message, or idea, about the real world (tenor).

Allegories often mirror characters and events from real life to comment on them indirectly.

To return to our discussion of Orwell’s Animal Farm, the story of the animal’s rebellion and Napoleon’s rise to power (the vehicle) carries the message about the real world example of Stalin’s rise to power and his usurpation of the Russian Revolution (the tenor).

Orwell’s allegory has several incidents occur in the plot that mirror real-world events: for example, the building of the windmill and its subsequent collapse represents one of Stalin’s disastrous five-year plans to rapidly industrialise Russia.

Remember, while an allegory may bear some similarities to a metaphor, it is not a metaphor.

Analysing an allegory is a similar process to analysing a metaphor, only the scale is larger – allegories can run for a few sentences through to the length of the text you’re reading or viewing.

The size of the allegory doesn’t change the process of identifying it, but it does mean you may need to be more patient and will definitely need to be more attentive when you’re reading your text to spot it and understand it.

Let’s look at an overview for analysing an allegory. If you feel that your narrative includes, or is, an allegory, you must:

Now we understand the overview of the process, let’s look at this as a step-by-step process. So we can be practical, we’ll consider Authur Miller’s play The Crucible as an example:

Arthur Miller’s play recounts the events of the Salem Witch Trials that occurred between 1692 and 1693. During the trials, the members of the town turned on another and denounced each other for witchcraft. By the end of the trails, 20 people had been hung.

Arthur Miller wrote this play during the 1950s, it was first staged on January 22nd, 1953 in New York. During this period, there was a heightened sense of tension between “Western Capitalists” and “Eastern Communists” as a consequence of the Cold War which had emerged out of the conclusion of World War 2.

In Act One, Miller starts making reference to the paranoia and animosity present in Salem and connecting it to events in his own context.

Miller frames the “witch hunt” occurring in his text as being a “perverse manifestation of the panic which set in among all classes when the balance began to turn toward greater individual freedom.” Clearly, he is suggesting there is a parallel between the two texts, but we need to be more specific about what that connection is and how it is being depicted, allegorically, in his text.

Miller’s play is unusual in that it intersperses dramatic action with extensive essays and sections of prose describing the historical context and the atmosphere of the 1950s. One such passage occurs on pages 35-36, Miller writes:

| At this writing, only England has held back before the temptations of contemporary diabolism. In the countries of the Communist ideology, all resistance of any import is linked to the totally malign capitalist succubi, and in America any man who is not reactionary in his views is open to the charge of alliance with the Red hell. Political opposition, thereby, is given an inhumane overlay which then justifies the abrogation of all normally applied customs of civilized intercourse. A political policy is equated with moral right, and opposition to it with diabolical malevolence. Once such an equation is effectively made, society becomes a coterie of plots and counterplots, and the main role of government changes from that of the arbiter to that of the scourge of God. The results of this process are no different now from what they ever were, except sometimes in the degree of cruelty inflicted, and not always even in that department. Normally the actions and deeds of a man were all that society felt comfortable in judging, The secret intent of an action was left to the ministers, priests, and rabbis to deal with. When diabolism rises, however, actions are the least important manifests of the true nature of a man. The Devil, as Reverend Hale said, is a wily one, and, until an hour before he fell, even God thought him beautiful in Heaven. |

In this passage, Miller makes it clear that he perceives a clear connection between the behaviours of the early settlers in Salem and the persecution of potential communists in America in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

The Crucible is commenting on the intolerance that can emerge in a society. To understand what society was being intolerant of, we need to know a little more about the period when Miller wrote the play.

Shortly before Miller began to research The Crucible, one of his friends was subpoenaed by an American Congressional Hearing. The Committee was known as the House Un-American Activities Committee, or HUAC. This committee was used to investigate figures who were accused of treason or loyalty to a foreign power. It was formed in 1938 but gained notoriety in the late 1940s and early 1950s when it was used to investigate actors and directors as part of an investigation into Hollywood.

The HUAC committee ruined the careers of many Hollywood actors, directors, or writers who were accused of having communist sympathies. HUAC became synonymous with Senator Joseph McCarthy, a Junior Senator from Wisconsin who launched several investigations into communists and homosexuals int he public service. While he never served on HUAC, he was a senator, he was the patron of a young congressman called Richard Nixon who did sit on the committee. The committee’s investigations often dovetailed with Senator McCarthy’s concerns.

One of the individuals called before the committee was an actor and director known as Elia Kazan. Kazan was a close friend of Miller’s until he testified before HUAC and named other directors and actors as being former communists. Kazan had initially been reluctant but ultimately testified against others from his industry that he had worked with.

We can deduce, then that there is a parallel between the characters in the text and those in real life:

Members of the House Un-American Committee/ Joseph McCarthy:

Witnesses who testified against their peers – such as, Elia Kazan, either freely or under duress:

Witnesses who defied the committee such as actor Lionel Stander:

We now understand how The Crucible is an allegory, but now we need to understand why Miller has written it in this way.

Allegories allow audiences to separate the ideas being discussed from the context they are from. MIller’s use of the Salem Witch trials allowed him to draw a parallel between an horrific event from America’s past and the present investigations into Hollywood. The Crucible is a tragedy, it depicts the ultimate fall and death of its protagonist, a flawed but heroic man who stood up to corrupt authority and paid for it with his life.

The Crucible allows viewers to understand the HUAC trials outside of the lens of political ideologies. Viewers can see how individuals turn on one another to protect themselves and their interests when placed under duress. This allegory depicts how social changes create situations where a change in social and political expectations produced a reactionary response, or as Miller said – “perverse manifestation of the panic which set in among all classes when the balance began to turn toward greater individual freedom.”

Now we need to communicate this in a structured manner. We must use a T.E.E.L structure to explain what we feel the allegory is stating:

You can find a more detailed explanation of using T.E.E.L in our post on paragraph structure (this post is part of our series on Essay Writing and shows you the methods Matrix English students learn to write Band 6 essays in the Matrix Holiday and Term courses).

Let’s use this T.E.E.L structure to write about allegory in The Crucible:

Let’s put this together into a complete piece of analysis about this allegory:

| Miller’s The Crucible is, superficially, an allegory about the House Un-American Committee (HUAC) and at a deeper level about any corrupt governing body that creates paranoia amongst is members or citizenry. Miller frames this issue in Act One, where he states in the interlude that “A political policy is equated with moral right and opposition to it with diabolical malevolence. Once such an equation is effectively made, society becomes a coterie of plots and counterplots and the main role of government changes from that of the arbiter to that of the scourge of God.” Here, Miller describes how ideology is used to pit citizens in a Manichean battle for the moral high-ground. In The Crucible, this division is between the characters Parris, Hathorne, and Danforth who embody the government (these characters paralleled the contextual figures of Nixon, McCarthy, and other members of HUAC) who were aligned against the citizens of Salem who were called before the court and resisted it – such as, Giles Putney and John Proctor (who reflected figures such as Lionel Stander and even Elia Kazan). Miller’s use of allegory is a powerful structural technique that allows audiences to understand conflicting political motivations within a society and the catastrophic consequences political corruption can have on a society. |

Now we have a solid grounding on how to analyse allegory, let’s look at one last example to ensure that you understand it thoroughly.

Let’s consider the poem Young Girl at A Window by Rosemary Dobson.

This poem describes a young girl waiting by a window and watching the world go by outside. But if you read this poem closely, it is an allegorical representation of a young girl passing through puberty. We can get a better sense of this by considering the first stanza:

“Lift your hand to the window latch:

Sighing, turn and move away.

More than mortal swords are crossed

on thresholds at the end of day;

The fading air is stained with red

Since Time was killed and now lies dead.

To go from being categorised as ‘a girl’ to being categorised as ‘a woman’ means that your social identity and definition change. The space between these categories is a dangerous or special time (depending on the cultural context). In Western culture, menarche signals that a change in social category is imminent as the category ‘woman’ is defined by the capacity to reproduce. Clearly, the young girl at the window is an allegory for young girls transitioning from childhood to adulthood.

The poem captures a moral spiritual transformation, where the character not only undergoes a physical change but also discovers a deeper sense of identity and time.

So, how do we discuss this?

We need to discuss the allegory, but we also need to discuss the other techniques in the stanza that demonstrate that the text is allegorical. Consider:

| The young girl is at a “[threshold] at the end of day” this signals that the poem is allegorical and suggests that the young girl is on the threshold between girlhood and womanhood. By extension, the visual imagery “air …stained with red” is a sunset (which would operate as a METAPHOR for the end of an era), while “stained with red” connotes bleeding, staining of clothing and sheets. Dobson is not so concerned with the messy material side of things, although the imagery does imply it. The poem renders the experience as a social and metaphysical discovery. In addition, ‘Crossing swords’ is an idiom for conflict, but it is important that the menarche is not simply a physical (“mortal”) change. The blood of the menarche is the blood of ‘killed Time’, where the death of Time is the death of the girl’s girlhood! ‘Young Girl at a Window’ allegorically presents the menarche as an experience of discovery of time itself, the passing of time. |

Learn how to utilise and discuss allegory in your English responses!

Produce insightful analysis & Band 6 essays!

Expert teachers. Band 6 resources. Proven results. Boost your English marks with our On Campus course.

Written by Matrix English Team

The Matrix English Team are tutors and teachers with a passion for English and a dedication to seeing Matrix Students achieving their academic goals.© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.