Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Select a year to see available courses

Science guides to help you get ahead

Science guides to help you get ahead

Struggling to get your head around analysing Emma? In this article, Part 2 in our series on Emma, we talk you through developing your study notes and analysing the themes and ideas in the text.

Guide Chapters

Join 75,893 students who already have a head start.

"*" indicates required fields

You might also like

Related courses

Join 8000+ students each term who already have a head start on their school academic journey.

Are you struggling with your Emma analysis like a Regency lady struggling to find a suitable man? You’re not alone! In this article, part 2 of our Ultimate Emma Study Guide, we discuss the key themes and from Austen’s classic so you can ace Mod B for your HSC!

In this article, we’re going to look at some key themes and how to analyse them for your Module B study.

If you haven’t already read it, you should check out our overview to Emma. It explains the connection to the Module and provides a detailed overview of the plot, the characters, genre, and key technique of Free Indirect Discourse.

Download an annotated Band 6 essay and see what makes a great essay, great!

Learn why HSC markers would score this essay highly! Fill out your details below to get this resource emailed to you. "*" indicates required fields

Download your annotated Module B Emma essay

Download your annotated Module B Emma essay

The secret to acing Module B is having comprehensive study notes. This isn’t to say, just go out and buy somebody else’s notes, that won’t help you. It is the process of creating notes as you study, for example answering the theory questions in your Matrix Theory Book while in class or watching a Matrix+ lesson that will help you learn the material.

It is well understood that it is the process of writing that helps us develop our ideas and remember them. The action of writing, especially by hand, changes the plasticity in our brains and helps us remember information. This is why many say that writing is the best form of thinking!

Initially, tables are a great way of compiling your initial notes.

You can either arrange them according to the characters:

| Character | Example | Theme | Technique | Effect |

| Emma | “I hope so–for at that time I was a fool!” | Transformation | Declarative statement | This declarative statement by Emma illustrates her awareness of how much she has changed over the course of the novel. She is now capable of objectively reflecting on her earlier behaviour. This is a good example of why this text can be classed as a bildungsroman. |

Or you can develop your notes by theme:

| Theme | Example | Technique | Effect | Relevance to Module |

| The foolishness of youth | It was foolish, it was wrong, to take so active a part in bringing any two people together. It was adventuring too far, assuming too much, making light of what ought to be serious—a trick of what ought to be simple. | Free indirect discourse | Emma comes to realise that she has made an error of judgement by interfering with other people’s love lives when she is so inexperienced herself. | Module B asks us to think about the textual integrity of the text. Austen’s deft and consistent use of free indirect discourse allows us to see how Emma matures throughout the novel. |

There is no right or wrong structure to use for tables, but you want to make sure that you are capturing the important information of:

Some students like to have several different tables collating this information, others just a single master table. You want to do whatever works for you.

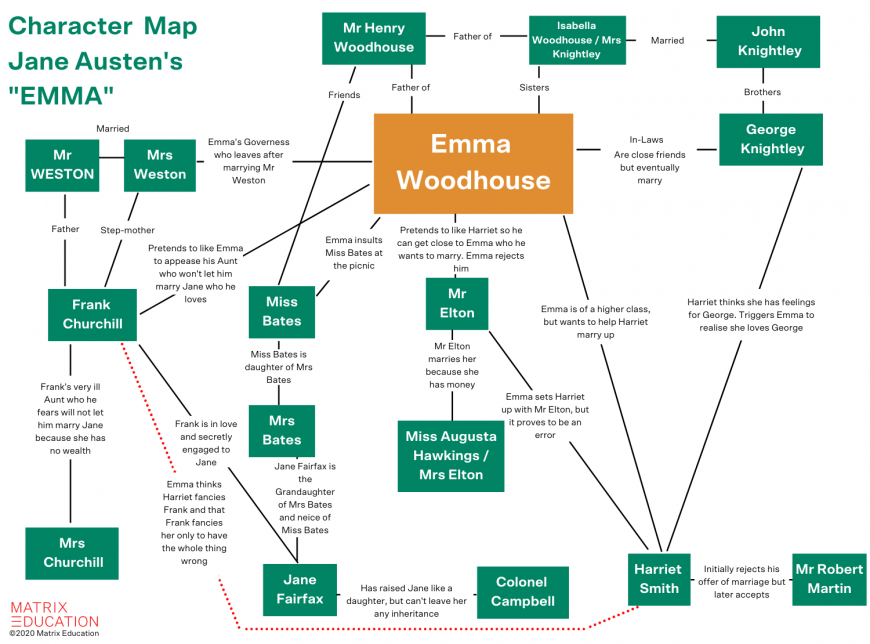

A good method some students use for developing their notes is by elaborating on them in journals and utilising colours and hand-drawn images. Something you may also want to consider is putting together a character map, like this:

The purpose of developing your notes and ideas is threefold:

Once you’ve got a decent set of study notes compiled, you’re ready to start writing practice responses.

The HSC requires you to write essays for all the Modules. Increasingly, NESA is setting more and more specific questions for each text. These questions often require students to consider a technique and an idea or theme from the text. Or they will provide a challenging statement about the text and ask you to respond to it.

For example, this is the question from the 2019 HSC, the first to reintroduce Emma into the syllabus:

A world of triviality, awkwardness and miseducation.

To what extent does this view align with your understanding of Emma?

In your response, make close reference to your prescribed text.

This is a challenging question because it presents three ideas about the text – triviality, awkwardness and miseducation – and asks you to consider whether this characterisation of the novel “aligns” with your understanding. In addition, it requires a nuanced response because it asks you to contemplate “to what extent” you feel this way.

You cannot sufficiently respond to this question with a memorised response. There is every chance that you may be asked to respond to quotations or discuss particular techniques.

Instead of writing a generic essay and memorising it, writing multiple practice response to a variety of questions will help you prepare for the challenges that the HSC, and Module B in particular, will throw at you.

You should write practice essays regularly. Once a week for English, ideally. That’s not one essay a week on Emma, but one a week out of all the set texts you’ve been set.

To be effective, you should follow this process:

If you’re looking for practice questions to get started, we have plenty in our list of Module B practice essay questions.

Now you know the process for compiling notes and writing practice responses, let’s get you started by giving you an overview of some of the key ideas Austen explores in her novel.

We provide students with detailed theory books, insightful lessons, and practical feedback to help students improve their marks like Mr Knightly improves Emma!

Learn how to write Band 6 HSC responses in English

Expert HSC teachers, detailed feedback, and comprehensive resources. Learn with Matrix+ online English courses.

Now you know the best practices for producing your study notes, you want to start unpacking the key ideas in Emma. What are the main ideas in Emma? Let’s have a look.

Emma is not nearly half as smart and knowledgeable as she thinks she is. This plot is what makes Emma a bildungsroman the narrator informs early on that:

“The real evils, indeed, of Emma’s situation were the power of having rather too much her own way, and a disposition to think a little too well of herself; these were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at present so unperceived, that they did not by any means rank as misfortunes with her.”

Emma is a young lady who feels that she’s is the smartest person in the room but is wholly unaware of her own shortcomings. This quotation is important as it foreshadows much of the action of the text. As Emma doesn’t see her shortcomings and values herself so highly, she makes a series of egregious errors that embarrass her and those around her.

In addition, Austen employs understatement here. The “real evils”, “having rather too much her own way”, and “to think a little too well” all have has a slightly ironic tone and, on first reading, don’t immediately seem to be as significant as they are.

Emma is not the only naive youth in the text. Frank Churchill is manipulative and plays games in a foolish way, jeopardising his relationship with Jane Fairfax.

Emma’s mate, Harriet is also foolhardy. Mr Knightley observes of her friendship with Harriet Smith that,

“I think [Harriet Smith] the very worst sort of companion that Emma could possibly have. She knows nothing herself, and looks upon Emma as knowing every thing. She is a flatterer in all her ways; and so much the worse, because undesigned. Her ignorance is hourly flattery. How can Emma imagine she has any thing to learn herself, while Harriet is presenting such a delightful inferiority?”

In Mr Knightley’s dialogue, he contrasts Emma with Harriet and draws attention to their shared naivete. He uses the repetition of “flattery” to point out how Harriet’s youthful ignorance will bring out the worst of Emma’s pride and foolishness. The concluding rhetorical question emphasises how similar they are in folly, if not class.

Emma begins to realise her foolishness in varying places throughout the novel. After her Mr Elton tries to woo her, rather than Harriet, Emma realises the mistake she has made. The narrator states that,

“The first error, and the worst, lay at her door. It was foolish, it was wrong, to take so active a part in bringing any two people together. It was adventuring too far, assuming too much, making light of what ought to be serious—a trick of what ought to be simple. She was quite concerned and ashamed, and resolved to do such things no more.”

Here the metaphor or idiom of the error “at her door” emphasises how Emma is at fault in the failed match with Mr Elton. The use of free indirect discourse where Emma notes how she was “foolish” and “wrong” represents her new awareness of her error. Austen employs tricolon where Emma chastises herself for “adventuring too far, assuming too much, making light of what ought to be serious.” Finally, Emma’s closing resolution where she “resolved to do such things no more” illustrates to the audience how Emma’s intelligence allows her to learn from her mistakes and grow as an individual.

One of the central concerns of Austen’s novels are the limited choices facing women during the Regency period. Women, even of wealthy means, only had a handful of options – marrying or remaining a wealthy spinster. We get a sense of this when the narrator lets us into Emma’s initial perceptions of Harriet,

[Emma] was not struck by any thing remarkably clever in Miss Smith’s conversation, but she found her altogether very engaging—not inconveniently shy, not unwilling to talk—and yet so far from pushing, shewing so proper and becoming a deference, seeming so pleasantly grateful for being admitted to Hartfield, and so artlessly impressed by the appearance of every thing in so superior a style to what she had been used to, that she must have good sense and deserve encouragement. . . . She would notice her; she would improve her; she would detach her from her bad acquaintance, and introduce her into good society; she would form her opinions and her manners. It would be an interesting, and certainly a very kind undertaking; highly becoming her own situation in life, her leisure, and powers.

Austen uses free indirect discourse so that we can get a sense of what Emma thinks of Harriet and how she feels that “she would notice her; she would improve her; she would detach her from her bad acquaintance, and introduce her into good society; she would form her opinions and her manners.” This illustrates how Emma feels that her only options as a young woman are to marry or help others to marry, to play at being a matchmaker.

It is important to note that here Emma is being very condescending. The use of free indirect discourse allows us to get a sense of how Emma is blind to the negative aspects of her plans and behaviour. The tricolon used when Emma muses how “it would be an interesting, and certainly a very kind undertaking; highly becoming her own situation in life, her leisure, and powers” develops the characterisation of her as young woman naive about her class and privilege, but also the limitations of her options in life.

When Mr Knightley chides Emma for interfering in Harriet’s romantic life with Mr Martin, he argues that,

Harriet’s claims to marry well are not so contemptible as you represent them. She is not a clever girl, but she has better sense than you are aware of, and does not deserve to have her understanding spoken of so slightingly. Waving that point, however, and supposing her to be, as you describe her, only pretty and good-natured, let me tell you, that in the degree she possesses them, they are not trivial recommendations to the world in general . . . Her good-nature, too, is not so very slight a claim, comprehending, as it does, real, thorough sweetness of temper and manner, a very humble opinion of herself, and a great readiness to be pleased with other people. I am very much mistaken if your sex in general would not think such beauty, and such temper, the highest claims a woman could possess.”

Here Mr Knightley contrasts Harriet and her demeanour with Emma’s to illustrate how Harriet has more positive qualities than Emma gives her credit for. This helps Emma come to realise her condescending behaviour and as a result not valuing Harriet’s positive qualities. Furthermore, Knightley’s final axiom that “such beauty, and such temper, the highest claims a woman could possess” starkly illustrates the limited options available to women – to behave well and to look beautiful in order to marry.

While the likes of Harriet and Emma have enticing options, young women with limited means were often limited in their potential matches or their occupations. Jane Foster is a good example off how limiting these choices were.

” Yes, indeed, there is every thing in the world that can make her happy in it. Except the Sucklings and Bragges, there is not such another nursery establishment, so liberal and elegant, in all Mrs. Elton’s acquaintance. Mrs. Smallridge, a most delightful woman!—A style of living almost equal to Maple Grove—and as to the children, except the little Sucklings and little Bragges, there are not such elegant sweet children anywhere. Jane will be treated with such regard and kindness!—It will be nothing but pleasure, a life of pleasure.— And her salary!—I really cannot venture to name her salary to you, Miss Woodhouse. Even you, used as you are to great sums, would hardly believe that so much could be given to a young person like Jane.”

In this quotation, Miss Bates, an older and slightly impoverished spinster herself, discusses the potential job as a governess Jane may have snared. The role of a governess, to those of the upper classes, was a lowly role. Miss Bates uses effusive language to describe the wealth of Mrs. Smallridge, Jane’s possible future employer, comparing it to be a “style of living almost equal to Maple Grove.” And while she suggests that “It will be nothing but pleasure, a life of pleasure” if she takes this role, it is clear that it is a position of servitude. Emma hints at this perception when she states that, “if other children are at all like what I remember to have been myself, I should think five times the amount of what I have ever yet heard named as a salary on such occasions, dearly earned.”

Marriage, then, was the best avenue for social mobility and economic security for the women in Austen’s novel. Emma humorously alludes to this when she considers the idea of Harriet marrying Mr Martin:

“Dear affectionate creature!—You banished to Abbey-Mill Farm!—You confined to the society of the illiterate and vulgar all your life! I wonder how the young man could have the assurance to ask it. He must have a pretty good opinion of himself.”

The loaded diction of “banished” that Emma uses illustrates the importance she places on marrying well. This quotation also highlights her snobbish characteristics when she describes Mr Martin and his peers disparagingly as “the society of the illiterate and vulgar.”

Emma goes on to try and enunciate the balance that needs to be struck when trying to find a match. She unequivocally states that,

“A woman is not to marry a man merely because she is asked, or because he is attached to her, and can write a tolerable letter.”

This aphorism shows Emma’s insight. This observation conveys the growing desire for romance in marriage as well as the opportunity it offers women to have social mobility.

Emma, herself, takes the position that,

“I have none of the usual inducements of women to marry. Were I to fall in love, indeed, it would be a different thing! but I never have been in love; it is not my way, or my nature; and I do not think I ever shall. And, without love, I am sure I should be a fool to change such a situation as mine. Fortune I do not want; employment I do not want; consequence I do not want: I believe few married women are half as much mistress of their husband’s house as I am of Hartfield; and never, never could I expect to be so truly beloved and important; so always first and always right in any man’s eyes as I am in my father’s.”

This proclamation shows Emma’s awareness of her own wealth and social position. She is in a privileged position, as the unmarried daughter of a wealthy father, noting through contrast that “few married women are half as much mistress of their husband’s house as I am of Hartfield.” Emma employs tricolon again to show the height of her position wherein, “fortune I do not want; employment I do not want; consequence I do not want.” She is also keenly aware of how her position within a household would change if she were to marry. She articulates this through repetition when she surmises that “never, never could I expect to be so truly beloved and important; so always first and always right in any man’s eyes as I am in my father’s.”

Class is a constant concern throughout Austen’s novels. While the upper classes are the focus of the texts, Austen takes great pains to contrast the wealth with the “well-bred,” often drawing attention to the moral failings of those who have money or have rapidly acquired it and contrasting those failings to the moral superiority of those from the lower classes. IN Emma, we see this in Mr Martin, the loquacious Miss Bates, and Jane Foster.

As Emma is an upper-class ‘young lady,’ raised to demonstrate good breeding and appropriate behaviour, she is our lens and moral compass for what is appropriate or vulgar behaviour. After a particularly unpleasant interaction with Mrs Elton, she rants that

“Insufferable woman!” was her immediate exclamation. “Worse than I had supposed. Absolutely insufferable! Knightley!—I could not have believed it. Knightley!—never seen him in her life before, and call him Knightley!—and discover that he is a gentleman! A little upstart, vulgar being, with her Mr. E., and her caro sposo, and her resources, and all her airs of pert pretension and under-bred finery. Actually to discover that Mr. Knightley is a gentleman! I doubt whether he will return the compliment, and discover her to be a lady. I could not have believed it! And to propose that she and I should unite to form a musical club! One would fancy we were bosom friends! And Mrs. Weston!—Astonished that the person who had brought me up should be a gentlewoman! Worse and worse. I never met with her equal. Much beyond my hopes. Harriet is disgraced by any comparison.”

The exclamation, “insufferable woman!”, highlights how Emma feels that all the wealth in the world will not give somebody vulgar good manners. While there is a degree of irony here (Emma, herself, can be vulgar and ill-mannered at times). Emma discusses the signifiers and shibboleths that denote good breeding:

Emma employs a particular sarcastic tone when she refers to Mrs Elton’s fondness for faux-Italian expression “caro sposo.” The implication being that a well-bred woman would know the correct Italian – caro marito or amato amrito.

However, while Emma might see herself as the protector of manners and etiquette in Highbury, she is not without her own prejudices and snobbery. She is particularly scathing towards farmers and manual labourers. Proclaiming of Mr Martin that,

“A young farmer, whether on horseback or on foot, is the very last sort of person to raise my curiosity. The yeomanry are precisely the order of people with whom I feel I can have nothing to do. A degree or two lower, and a creditable appearance might interest me; I might hope to be useful to their families in some way or another. But a farmer can need none of my help, and is therefore in one sense as much above my notice as in every other he is below it.”

Here, Emma’s class prejudice manifests in a condescending tone when she tells Harriet that farmers are not the types she, or any woman of class, should look to marry. Austen uses this aspect of the marriage plot to illustrate how the petty prejudices of the upper classes blind individuals to the noble qualities that those of the lower classes possess. While initially deriding Mr Martin as part of the “yeomanry” – something only slightly better than a peasant in her estimation – she later comes to agree with their match and “most sincerely wish[es] them happy.” Emma’s contrition a signal that upper-class prejudices were often unfounded.

Along with class, Emma explores pride and vanity. The Bildungsroman form of the text heightens our awareness of Emma’s flaws. One of the most obvious is her pride and vanity – something she is quick to accuse Mrs Elton of having too much of. Emma is often more than aware of her own social position and sees it as something that sets herself above others in society. She argues that,

“A single woman, with a very narrow income, must be a ridiculous, disagreeable, old maid! the proper sport of boys and girls; but a single woman, of good fortune, is always respectable, and may be as sensible and pleasant as anybody else.”

In this aphorism, Emma argues that her wealth and position make affords her the opportunity to be respectable spinster. To make her point she contrasts herself to a woman of “narrow income” who could only become “a ridiculous, disagreeable, old maid.” Austen develops irony here because Emma makes the assumption that her wealth and position will make her “as sensible and pleasant as anybody else” an assertion made out of youthful naivete.

Later in the novel, Emma begins to understand her own failings of pride and vanity. One of her strongest qualities is her ability to self-reflect (a quality that you, as an HSC student, should embrace for yourself if you want to ace your HSC!). Emma’s reflection on her relationship and rivalry with Jane is a good example of this:

“Why she did not like Jane Fairfax might be a difficult question to answer; Mr. Knightley had once told her it was because she saw in her the really accomplished young woman, which she wanted to be thought herself; and though the accusation had been eagerly refuted at the time, there were moments of self-examination in which her conscience could not quite acquit her.”

In this quotation, Austen has employed free indirect discourse to shift us from the narrator’s observation of Emma’s pride and vanity into Emma’s own awareness of it. Austen uses understatement and low modality language to convey how Emma understood that she was jealous of Jane but just had trouble admitting it. It’s also interesting that Austen has employed the legal jargon of “accusation,” “refuted,” “self-examination,” and “acquit” to convey this process of reflection, adding to its sense of honesty and objectivity.

The Regency Period saw many young couples starting to pair off out of love rather than merely at the wishes of their parents. Austen reflects this social change in her novels by she approaches the concept of love. Emma’s conversation with her friend and former governess, Mrs Weston, gives us insight into how love was becoming a much bigger consideration for young women and men. In it, Emma voices her displeasure at Frank Churchill’s behaviour, stating,

“I have escaped; and that I should escape, may be a matter of grateful wonder to you and myself. But this does not acquit him, Mrs. Weston; and I must say, that I think him greatly to blame. What right had he to come among us with affection and faith engaged, and with manners so very disengaged? What right had he to endeavour to please, as he certainly did—to distinguish any one young woman with persevering attention, as he certainly did—while he really belonged to another?—How could he tell what mischief he might be doing?—How could he tell that he might not be making me in love with him?—very wrong, very wrong indeed.”

Emma is upset because she has just discovered that Frank is engaged to Jane. However, what is really interesting here is the language she uses to describe her feelings and and her anger at being deceived.

Emma employs diction like “escaped” to describe her relief at not falling further in love with him. And she uses zeugma and wordplay in the rhetorical question, “What right had he to come among us with affection and faith engaged, and with manners so very disengaged?”, to illustrate how he wilfully deceived her and the other women of Highbury. Then, the anaphora of “what right had he” and “how could he tell” further emphasises her anger and dismay at this behaviour. The series of rhetorical questions reach their apotheosis when Emma comes to her real point in the last one – “How could he tell that he might not be making me in love with him?”. A point finally emphasised with the repetition of “very wrong.”

This reaction illustrates to us, and her, the importance of love when finding a husband or wife to both Austen and her characters.

We get to see this happen to Emma when she has the moment of realisation that she is in love with Mr Knightley. Austen conveys this with a combination of techniques, showcasing her literary skills:

“A few minutes were sufficient for making her acquainted with her own heart. A mind like hers, once opening to suspicion, made rapid progress; she touched, she admitted, she acknowledged the whole truth. Why was it so much worse that Harriet should be in love with Mr. Knightley than with Frank Churchill? Why was the evil so dreadfully increased by Harriet’s having some hope of a return? It darted through her with the speed of an arrow that Mr. Knightley must marry no one but herself!”

This example mixes:

Austen uses this combination of techniques to take us inside Emma’s experience of this epiphany of love. We get to see Emma reflect on her own jealousy and use that to come to the realisation of how she really feels about Mr Knightly.

Why is this so important?

Emma has not only found somebody she wants to marry, she wants to marry them because she is in love!

A bildungsroman is a narrative that shows the transformation of an individual from naive to worldly. The idea of transformation, as it is explored in Emma, brings together the form and content of the text.

In the final chapters of the novel, Emma makes two important realisations (among others) that demonstrate her transformation.

The first, and arguably the most important, is when she comes to the conclusion that,

“With insufferable vanity had she believed herself in the secret of everybody’s feelings; with unpardonable arrogance proposed to arrange everybody’s destiny. She was proved to have been universally mistaken; and she had not quite done nothing—for she had done mischief. She had brought evil on Harriet, on herself, and she too much feared, on Mr. Knightley.—Were this most unequal of all connexions to take place, on her must rest all the reproach of having given it a beginning; for his attachment, she must believe to be produced only by a consciousness of Harriet’s;—and even were this not the case, he would never have known Harriet at all but for her folly.”

This reflection shows a significant transition away from her perception of herself as the ideal match-maker. Here, she realises with mortification how naive and self-centred she has really been. In this extract, Austen once again uses free indirect discourse to illustrate how Emma comes to this conclusion and also employs em-dashes to connote the successive realisations she is having. This is important as we get to see, in real-time, how Emma matures and becomes the woman she wants to be and thinks she is.

Later, in conversation with Mr Knightley, Emma demonstrates this transformation by admitting to her mistakes rather than merely alluding to what she might do. instead of stating, she acts, declaring that,

“I hope so–for at that time I was a fool.”

By admitting to being “a fool,” Emma is demonstrating the maturity and self-awareness that Mr Knightley has been chiding her for throughout the novel. This admission is important as it shows how by maturing, Emma is more amenable about admitting her mistakes and is less argumentative and obdurate when receiving criticism. This is a decidedly different response to, say, when Mr Knightley criticised her for interfering in Harriet’s romantic life or insulting Miss Bates.

Written by Matrix English Team

The Matrix English Team are tutors and teachers with a passion for English and writing, and a dedication to seeing Matrix Students achieving their academic goals.© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.