Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Select a year to see available courses

Science guides to help you get ahead

Science guides to help you get ahead

Are you struggling to make sense of Jane Austen's comedy of manners? Don't worry, in part 1 of our ultimate Emma study guide, we'll explain the plot, characters, and key features.

Guide Chapters

Join 75,893 students who already have a head start.

"*" indicates required fields

Related courses

Join 8000+ students each term who already have a head start on their school academic journey.

Are you confused by the marriage plot, free indirect discourse, or Regency high society manners and protocols? Don’t worry, many from Austen’s time were too! In this article, we are going to give you the ultimate Emma study guide to help you with your understanding of Emma, its themes, and techniques.

In this article, the first of two, we’re going to explain what you need to know to study Emma for Module B. We’ll:

In the second article, we give you a guide to analysing the techniques and themes in Emma.

To get started, let’s explore what Module B asks of you and how this relates to the study of Jane Austen’s novel, Emma.

Download an annotated Band 6 essay and see what makes a great essay, great!

Learn why HSC markers would score this essay highly! Fill out your details below to get this resource emailed to you. "*" indicates required fields

Download your annotated Module B Emma essay

Download your annotated Module B Emma essay

Emma is a novel about a young woman, the eponymous Emma Woodhouse, and her development and education as a young woman. The narrative follows her from when her governess leaves her to go and marry until she herself finds love with her brother-in-law, George Knightley.

The plot is rather simple in that it is a bildungsroman that shows Emma’s development to a naive young woman who won’t marry to an enlightened young woman in love Mr Knightley. However, the twists and turns along the way make it rather complex and sophisticated.

The novel opens with Emma’s governess, Miss Taylor, marrying Mr Weston. She introduced them and feels this makes her an effective matchmaker. She decides to pursue this as a hobby. Against the advice of her dad (Mr Woodhouse) and brother-in-law (Mr George Knightley), Emma tries to play matchmaker for Harriet Smith.

Harriet is infatuated with a local farmer, Mr Martin. Emma convinces her to reject the proposal. Emma tries to set Harriet up with Mr Elton. They hit it off, but George is sceptical of the match. It is revealed that Mr Elton is really trying to hook up with Emma and is using Harriet’s attention as a means to get close to Emma. Emma rightly rejects him.

Shortly after, Mr Elton shows his true colours and quickly marries a woman of lesser income than Emma – Mrs Augusta Hawkins. Mrs Elton is a boastful and ill-mannered woman who illustrates the distinction between people of “good breeding” (those born into wealth and raised properly) and those who are new money. This leaves Harriet gutted as she really fancied Mr Elton and thought him to be a nice bloke.

Frank Churchill arrives in town for a fortnight and becomes instantly popular. He has been in Highbury very little because of the demands of his aunt. George warns Emma about Frank, suggesting that he is not what he seems and of poor character for not attending his father’s wedding.

Jane Fairfax also arrives in town for a few months to stay with her Aunt, Mrs Bates. Jane is beautiful, intelligent, and quite talented. But she has little wealth and few prospects in marriage. Emma takes a dislike to her because she draws so much attention. She is jealous of the praise that she draws for her musical performances. Emma begins to come around when Mrs Elton patronisingly promises to get her a position as a governess.

Emma suspects, wrongly, that Jane and Mr Dixon are attracted to one another. She confides this, ironically, to Frank, who agrees to conceal their engagement. Emma begins to fall for Frank, but then decides her feelings aren’t like that.

The Elton’s begin to be horrible to Harriet and snub her at the Weston’s ball. Being the gentleman that he is, George asks Harriet to dance. This surprises Emma, George isn’t the dancing type and she liked the way he tore up the dancefloor.

The following day, having been cornered by gypsies who were aggressively seeking alms, Harriet faints and needs to be carried back to the house by Frank. Emma misinterprets this and thinks that Harriet is in love with Frank. Compounding the drama, Emma thinks that Frank is trying to court her. George voices his thought that something seems to be going on between Jane and Frank, spying the real truth, but Emma disagrees. Emma continues to think Frank is into her.

At a picnic, Emma insults Miss Bates for talking too much. The scene damages Emma’s reputation and ruins the picnic. Emma is scolded by George for her actions. The following day she goes to ask forgiveness from Miss Bates. This impresses George.

Emma learns that Jane has accepted a governess position and tries to visit her. Jane refuses her visit. Frank returns and reveals to his father and stepmother that he is engaged to Jane. it comes out that he kept up a ruse to avoid upsetting his aunt. jane becomes upset, the secretive nature of the engagement has upset her. She has, it turns out, called the engagement off – this is the reason for her “illness” and refusal to take Emma’s visit. Frank’s uncle agrees to the match and it is back on and publicly announced.

Emma is surprised and upset. She fears that this will upset Harriet. However, Emma has it wrong, Harriet is in love with George. Harriet’s desire for Mr Knightley makes Emma realise that she’s really in love him. Emma and George talk, he reveals his feelings and proposes. Emma accepts. Rounding out the ending, Mr Martin proposes again and Harriet accepts. Jane and Emma make up. Frank and Jane set a date to wed.

The novel concludes with Emma’s marriage to George.

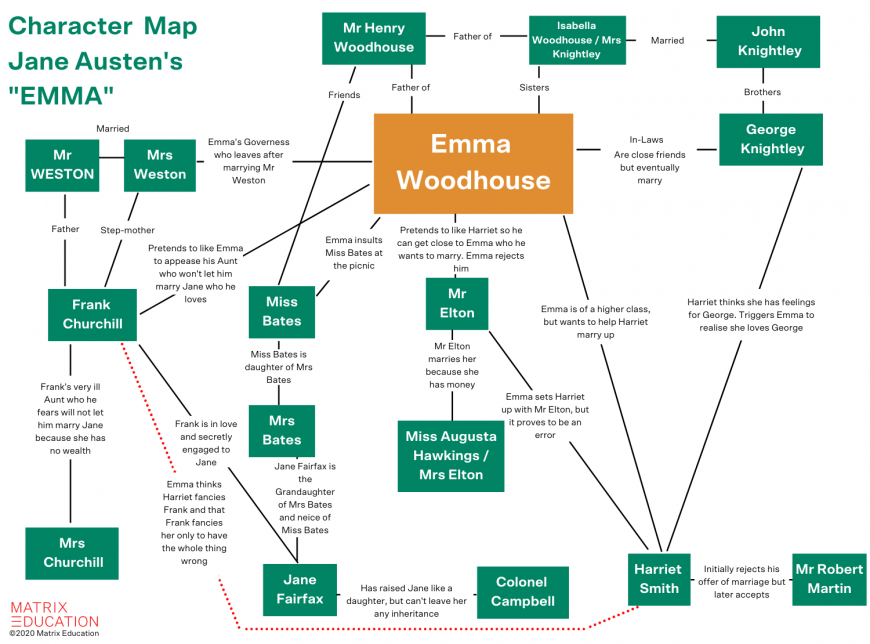

Okay, you’re right. That’s quite a complicated plot with quite a cast of characters.

To help you understand it and follow who’s who, we’ll look at the characters in more detail. Here is a character map that shows their relationships to one another.

Okay, that’s quite a complicated plot with quite a cast of characters. To help you understand, let’s have a look at the main characters:

The protagonist of the novel. Emma is a wealthy young woman who lacks guidance. She is well-meaning but snobbish and a touch condescending. Her biggest failings are her naivete and pride.

She tends to think she knows far more than she actually does. This is compounded by her unwillingness to study anything in detail. as a consequence, she often takes of half-cocked only to make a later error of judgement.

She is headstrong and determined that she will never marry. Over the course of the novel, this changes as she tries to play matchmaker for other couples, misconstrue the advances and intentions of others, and eventually falls in love with George Knightly – her best mate and brother-in-law.

George, while 16 years Emma’s senior, is her best friend. He is also her brother-in-law (being the brother of John Knightly, who is married to Emma’s sister Isabella) and most attendant critic. He is a kind and caring man. He is often very perceptive and always has other people’s feelings in mind. He is responsible for a crucial moment in the text when he chastises Emma for insulting Miss Bates at the picnic.

He is most upset when Emma interferes in the relationship between Harriet and Mr Martin. Further, he is the first to surmise that Mr Elton is more the cad than he appears. George is especially critical of Frank. he doesn’t trust Frank’s motives, especially when Emma seems to fall for him

A happy go lucky bloke and like by almost everybody. The son of Mr Weston, he took his Aunt’s name at her assistance.

He likes to dance and lives a relatively carefree existence. Although he wasn’t born into a wealthy family, he was adopted into one when he was taken into his aunt’s (Mrs Churchill) family. He is often absent, having left to tend to his ailing aunt. He is perceived by many, especially George Knightly, to be selfish because he fails to turn up to his father’s wedding.

He is playful and a little flirtatious with several women in Highbury but this is a cover for his secret engagement to Jane Fairfax. He can’t be open about his relation to due to his aunt’s likely objection to their relationship. As Jane is without means, she’d be a poor match for her adopted son.

A beautiful young woman who was orphaned and raised by Colonel Campbell and his wife. She has little family in Highbury, only Miss Bates, her aunt. While Colonel Campbell has raised her like his own daughter, he is unable to leave her an inheritance. Because she has no income, her marriage prospects are very poor. She is very principled and moral.

While she loves Frank Churchill, their secret engagement upsets her and leads them to quarrel. If she doesn’t marry, she will likely become a governess, which is only a magical role if you are Mary Poppins. At the end of the novel, it is announced that she will wed Frank Churchill.

Conspicuous by their consistent absence, they add to the ongoing tension in the text. They have raised Jane Fairfax and seen to her education. They are holidaying in Ireland for much of the novel and their delayed return is a point of anxiety at several junctures in the text.

A young, attractive but not particular sophisticated or worldly woman. She is 17 and becomes a project for Emma who wants to help her marry up. Emma and Harriet meet because Harriet is a border with her own rooms at the local private school. Harriet’s father is a tradesman, and while note of the upper class is quite successful.

She is initially infatuated with Mr Martin, whom she rejects at Emma’s suggestion. She then falls for Mr Elton who only pretends to like her to get close to Emma. She spends time with Frank Churchill, leading Emma to think she fancies him. She has fleeting infatuations with others. Most notably, she falls for Mr Knightley. Her admission of this to Emma is a catalyst for Emma’s engagement to George.

She eventually marries Mr Martin when he proposes a second time.

A local farmer. He is quietly successful, but not a man of the upper classes. He is caring and well-spoken and Harriet is initially infatuated with him. He proposes to Harriet, but at Emma’s behest she knocks his proposal back. At the end of the novel, he proposes again and she accepts.

The new vicar of Highbury. He is young and ambitious. He is a good-looking fellow who appears to be polite and well-mannered. Over the course of the text, this is shown to be a facade. He is in actuality quite manipulative and very much a “gold digger.” He cosies up to Harriet, leading Emma and Harriet to believe that he is infatuated with her. In reality, he was trying to make a move on Emma, who rejects him. He marries Augusta Hawkins, a woman with less income, after being rejected by Emma.

Augusta Hawkins is a woman of new wealth. She lacks the manners and society upbringing that many in the Highbury circle expect of people, especially women. She often does things that show a lack of decorum – referring to people by their Christian names, patronising them, boasting about her wealth. She expects to be treated as a member of the upper classes but does not behave as one. She stands as a foil to the “good breeding” and manners of many other women in the text.

Anne Taylor was Emma’s governess for 16 years. She is Emma’s closest confidant and loves Emma dearly. She visits the Woodhouses regular. She is often a mother figure to Emma and tries to offer her guidance and a voice of reason.

Frank Weston’s father to the first Mrs Weston – his first wife who passed away. Frank was raised by his late wife’s brother and brother’s wife because of Mr Weston’s position in the militia. He is a friendly and sociable chap.

Miss Bates is a rambunctious spinster who likes to talk. Miss Bates was the vicar’s daughter, but Miss Bates and her mother have fallen on hard times since the death of her father. She lives with her mother in rented rooms. They receive alms and charity from the wealthy people of Highbury.

Emma’s father, a widower. Mr Henry Woodhouse is a sickly man, but loathe to interfere in the affairs of others. He dotes on his daughters and appoints Miss Taylor to educate Emma.

Emma’s sister. 7 years older than Emma, Isabella lives in the city of London. She has a similar set of health issues to her father.

Mr Frank Churchill’s ailing but very wealthy aunt. Frank is sure that she will object to his relationship and marriage to Jane Fairfax. Frank fears, probably rightly so, that Mrs Churchill will deem Jane a poor match because of her lack of means and prospects. This, of course, being a time of couples marrying mostly for social mobility and only rarely, although increasingly more, for love.

Mrs Churchill demands a lot of Frank’s time and attention. Her death is the catalyst enabling Frank and Jane to reveal their relationship to the Westons and then everybody else.

Module B is all about the close study of texts. This means that you need to analyse a text in detail, in this case, the novel, Emma, and then consider it as a whole and in relation to its context, reputation, and lasting appeal or value.

To help you to understand this, NESA had given you some fairly detailed (but not always) instructions as to how you should go about this. These are the rubric statements. Let’s go through the key ones and see what they mean:

“In this module, students develop detailed analytical and critical knowledge, understanding and appreciation of a substantial literary text. Through increasingly informed and personal responses to the text in its entirety, students understand the distinctive qualities of the text, notions of textual integrity and significance.”

This means that you are not simply analysing a specific chapter or page of Emma, you are expected to analyse Austen’s text in its entirety. You have to evaluate the texts’ relevance to contemporary society and consider its cohesiveness as a whole.

When you are doing this, you must examine the text’s “distinctive qualities“. That means figuring out which aspects of Emma’s construction makes it a lasting text:

There’s a lot to consider there. But that is not all.

You also need to see whether Austen has written Emma with textual integrity. What’s textual integrity, you ask?

NESA defines textual integrity as having these elements:

Once you have a solid understanding of Emma you’ll be better positioned to understand whether or not it has textual integrity (hint, it does!).

To read more about textual integrity, check out our Essential Guide to Textual Integrity.

You also need to contemplate the text’s “significance”.

Significance refers to the importance or relevance of a text to a particular time and place (context). Texts might be historically significant, but it does not mean that they will always be relevant to future contexts.

As such, a text’s significance can fall or rise depending on what is happening in that particular context. You need to think about what made the text significant in the past and if this significance is ongoing, and why?

“Central to this study is the close analysis of the text’s construction, content and language to develop students’ own rich interpretation of the text, basing their judgement on detailed evidence drawn from their research and reading.”

You need to analyse the text’s form, ideas, themes, technique and style.

“Your own rich interpretation” means that you need to formulate arguments that you believe based on “detailed evidence” from “research and reading“.

This means that as you re-read Emma, discuss it with other people (like your Matrix teachers and peers) and Google aspects of the text you struggle with, your opinion may change! That is OK. This is what happens when you learn more about a thing, your original understanding and opinions change.

As long as they are your own opinions and arguments that you genuinely believe in, you are developing your “own rich interpretation”.

“In doing so, they evaluate notions of context with regard to the text’s composition and reception;“

Context refers to what is happening at a particular time and space, including personal, environmental, historical, social and political contexts. These ideas and values influence a text’s composition.

To evaluate the notions of context, you need to:

“investigate and evaluate the perspectives of others; and explore the ideas in the text, further strengthening their informed personal perspective”

We went on about how you need to develop your own personal opinions and arguments. However, it is also important that you see what other people think about Emma.

This means that you need to:

Doing this will help you develop depth in your perspective about your text, and subsequently your arguments.

“Students have opportunities to appreciate and express views about the aesthetic and imaginative aspects of the text by composing creative and critical texts of their own. Through reading, viewing or listening they critically analyse, evaluate and comment on the text’s specific language features and form. They express complex ideas precisely and cohesively using appropriate register, structure and modality.”

This rubric point refers to your Year 12 assessments.

As such, you may be asked to respond to Emma in a variety of ways like persuasive essays, multimodal presentations, imaginative recreations.

Each of these modes of assessments will require different approaches. You need to consider different registers, structures and modality.

To see more on how to analyse texts, you should read Part 2 of our Beginners’ Guide to Acing HSC English: How to Analyse Your Texts.

Now you know what you need to be looking at and considering in Austen’s novel, let’s have a look at some of the key ideas and elements of the text.

As you’ve hopefully noticed, much of the action and excitement in Emma centres on the manners and etiquette of Regency society. To understand why this is a source of humour, irony, and plotting, we need to consider what was happening in the Regency period.

The Regency is a period of English history running from 1811-1820. The Regency began when King George III abdicated the throne in favour of his son George IV due to mental health issues.

The Regency was a period of contradictions – upper-class wealth and growth in the arts set against the Napoleonic war and class stratification.

Austen is largely concerned with the upper classes and their values and attitudes. She highlights how those with money don’t necessarily have good etiquette, manners, or morality. The purpose of her novels often seems to be educating readers to what is right, ethical, and moral and what is not.

Like much of Europe, England has been a class society since the Medieval period. Unlike other parts of the world that were grappling with the redistribution of wealth and breaking down of class barriers, England entrenched its class stratification during the Regency.

Why?

The success of colonisation and the rise of merchants and industrialists lead to many outside of the upper class and nobility accruing wealth rapidly and in significant sums. Many in the upper classes were resentful of these people, the so-called Nouveau Riche, who they perceived as ill-mannered upstarts.

One of the positives of the rise of the nouveau riche was proof that class mobility was now possible. However, those with traditional wealth, or “old money”, liked to differentiate themselves to these people. So, while the middle class came into existence and marriage ceased to be the main means of class mobility, class stratification remained.

So, what’s the connection to Austen and Emma?

During the Regency, the upper classes – especially the older families, landed gentry, and nobility – sought to differentiate themselves from the newly wealthy. Manners, etiquette, and diction became the main symbols of the upper class.

People from traditionally wealthy families, such as Emma and the Woodhouses, were raised to understand proper etiquette and behaviour. This so-called “good breeding” included learning things like:

Many of the distinctions between characters of the upper class, lowerclass, and nouveau riche are illustrated through their etiquette and manners. When Emma and Mrs Elton are chatting in chapter 32, we see a good deal of such faux pas in action:

“I honestly said as much to Mr. E. when he was speaking of my future home, and expressing his fears lest the retirement of it should be disagreeable; and the inferiority of the house too— knowing what I had been accustomed to—of course he was not wholly without apprehension. When he was speaking of it in that way, I honestly said that the world I could give up— parties, balls, plays —for I had no fear of retirement. Blessed with so many resources within myself, the world was not necessary to me. I could do very well without it. To those who had no resources it was a different thing; but my resources made me quite independent. And as to smaller-sized rooms than I had been used to, I really could not give it a thought. I hoped I was perfectly equal to any sacrifice of that description. Certainly I had been accustomed to every luxury at Maple Grove; but I did assure him that two carriages were not necessary to my happiness, nor were spacious apartments.”

Here we see Mrs Elton brag about her wealth, repeatedly, and wholly become self-absorbed. This is the kind of behaviour that was very much frowned upon and tended to signify that the speaker was of the nouveau riche. Similarly, we witness some of her more grotesque, and ironic behaviour, when she speaks of the Tupman’s in chapter 36 who she describes as:

“[E]ncumbered with many low connexions, but giving themselves immense airs, and expecting to be on a footing with the old established families.”

Clearly, these are qualities which are very much like her own.

Emma is not above such slips of manners. Much of plot and humour in Emma stems from her inability to see her own flaws. One key scene is Emma’s insult to Miss Bates at the picnic in chapter 43 and apology in 44.

When jesting with everyone, Emma states to Miss Bates:

“Ah! ma’am, but there may be a difficulty. Pardon me —but you will be limited as to number —only three at once.”

While Miss Bates doesn’t immediately recognise the insult, that she is too talkative “a slight blush shewed that it could pain her.” This scene at Box Hill is important as it is one of the moments where readers, and Emma, get to understand that Emma is the not the kind and modest character she perceives herself to be.

The marriage plot is a staple in Austen’s novels. Marriage was a key means of social mobility prior to the Regency period. Austen, critical of this, often uses the marriage plot to critique the behaviour of the landed gentry and nouveau riche in her novels. Emma is a good example of this.

In many ways, Emma mimics the comedies of Shakespeare and the renaissance in that it concludes with a series of acceptable marriages that bring order to the community. At the conclusion of the text, Emma, Harriet, Jane, and Mrs Elton have all wed acceptable matches for their social classes.

While this is a satisfactory conclusion for the period, the plot turns and key confrontations highlight the narrow range of options that women from that period had. For the women in Austen’s novels, there are only a few starkly differentiated choices open to them:

The marriage plot in Emma, beginning as it does with Emma’s assertion that she “promise[s] to make [no matches] for herself,” highlights these choices. It also highlights that as a woman of significant means – £10,000 a year! – she has choices that other women, like Jane Fairfax, do not.

Jane Fairfax, orphaned and without means, is the sort of woman who would likely have faced life as a governess were it not for Frank. And while they do ultimately wed, it is only acceptable because Colonel Campbell has raised her with trappings of “good breeding”. Qualities that are on display with her high manners, modesty, and talents at the pianoforte!

The other thematic importance of the marriage plot lies in the character’s education.

Emma is a bildungsroman, a novel of personal education. In Emma, we see her develop and learn. Much of this happens at the hands of Mr Knightley. Her marriage to George, the man who shows her the error of her ways illustrates how a good match and marriage is educational and informational (although there are exceptions).

As a final note on the marriage plot, it is worth considering the marriages in the text:

A key aspect of Austen’s novels is her perspective and structure. Austen is a master of a style of the perspective known as free indirect discourse.

Austen writes in the 3rd-person, but uses free indirect discourse to allow us to get very close to characters’ perspectives.

Think of free indirect discourse as sitting just over a character’s shoulder and occasionally dipping into their thoughts.

Free indirect discourse is a style of writing where the narrator is positioned close to the characters, almost as if it is first-person narrative, while still being able to step back and allow us to see their strengths and flaws.

To understand how it works in Emma, let’s consider one of the earliest examples of free indirect discourse focused on Emma from chapter 3. But to illustrate how free indirect discourse works we’ll first rewrite it as direct speech, then indirect (reported) speech, before seeing how Austen wrote it:

‘Emma sat and observed Miss Smith and her conversation. “There’s nothing remarkably clever in Harriet, but she is engaging — not inconveniently shy, not unwilling to talk — and yet so far from pushing, shewing so proper and becoming a deference, seeming so pleasantly grateful for being admitted to Hartfield, and so artlessly impressed by the appearance of everything in so superior a style to what she had been used to, that she must have good sense. She deserves encouragement!” Emma said.’

In this direct speech reworking of the example, the character speaks their mind as a way of conveying their thoughts. This is impractical (and rude!) and not effective at allowing the reader into a character’s thoughts. We know what Emma says to herself, but we don’t see it as a reaction from her perspective.

Emma sat and observed Miss Smith and her conversation. She remarked to herself that there’s nothing remarkably clever in Harriet, but she is engaging — not inconveniently shy, not unwilling to talk — and yet so far from pushing, shewing so proper and becoming a deference, seeming so pleasantly grateful for being admitted to Hartfield, and so artlessly impressed by the appearance of every thing in so superior a style to what she had been used to, that she must have good sense. She deserves encouragement!” Emma said.

In this indirect speech example, we know more clearly that Emma is thinking and not speaking. We understand what she thinks of Harriet. But we are still at a remove from Emma’s perspective. The speech tag – “she remarked to herself” – reminds us of the presence of the narrator and separation from the character.

[Emma] was not struck by any thing remarkably clever in Miss Smith’s conversation, but she found her altogether very engaging — not inconveniently shy, not unwilling to talk — and yet so far from pushing, shewing so proper and becoming a deference, seeming so pleasantly grateful for being admitted to Hartfield, and so artlessly impressed by the appearance of every thing in so superior a style to what she had been used to, that she must have good sense and deserve encouragement.

In the original free indirect discourse quotation, we are taken into Emma’s perspective. This is important as it allows us to begin to see her flaws and her self-deception. What she’s actually proposing is quite condescending and manipulative. She’s implying that:

However, because Austen uses free indirect discourse, it is not immediately clear how unpleasant Emma’s plan and thought process is. Free indirect discourse allows us to see how “[t]he real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the power of having rather too much her own way, and a disposition to think a little too well of herself… however … they did not by any means rank as misfortunes with her.” Emma is a hypocrite and a bit of a snob, but free indirect discourse puts us so close to her perspective that it is only later in the novel that we begin to realise the true nature of her character.

A good exercise when studying Emma is to consider which characters have their thoughts rendered as free indirect discourse and which don’t (hint: who is the biggest positive moral influence on Emma?).

The Matrix Year 12 English Advanced Module B course for Emma will give you an in-depth understanding of the text with an expert instructor, exclusive resources, and in-depth feedback and discussion. Learn more!

Learn how to write Band 6 HSC responses in English

Expert HSC teachers, detailed feedback, and comprehensive resources. Learn with Matrix+ online English courses.

Written by Matrix English Team

The Matrix English Team are tutors and teachers with a passion for English and writing, and a dedication to seeing Matrix Students achieving their academic goals.© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.