Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Get HSC Trial exam ready in just a week

Get HSC exam ready in just a week

Select a year to see available courses

Science guides to help you get ahead

Science guides to help you get ahead

Still unsure of how to analyse metre? Well, you came to the right place! We will explain what metre is, show you different types of metre in poetry and show you how to analyse metre, step-by-step, with an example from Rosemary Dobson.

To understand what a metre is, you need to first know a ‘foot’ means.

A foot refers to the stressed and unstressed syllables in a word or words.

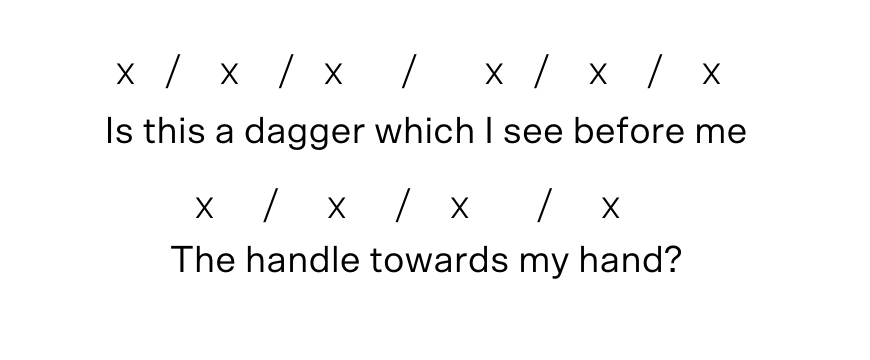

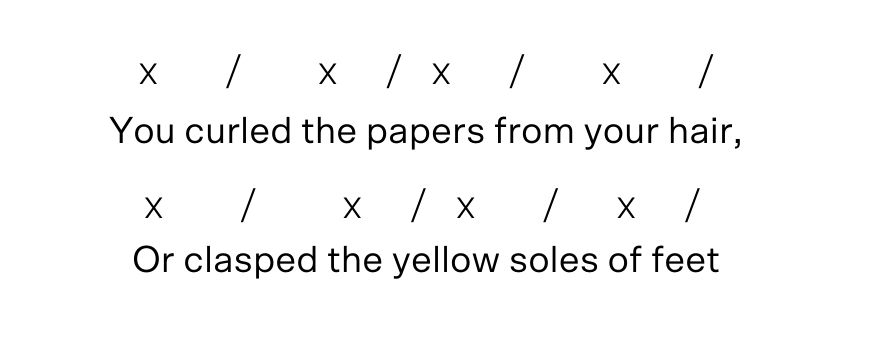

In poetry, a foot can have either two or three syllables. When distinguishing between the two, you can use ‘/’ to represent stressed syllables, and ‘X’ to represent unstressed syllables.

Remember, you should always read the line out loud to help you figure out the stressed and unstressed syllables.

Now that you understand the difference between stressed and unstressed syllables, let’s apply this to real words. Read them out loud and pay attention to the intonations:

Now, that you understand what a foot is, let’s see what is metre.

Metre is a pattern of feet (plural for foot). So, when we write a line with feet, we create a metre.

da-DUM is a foot, and da-DUM, da-DUM, da-DUM is a metre.

You see, a poet is able to create a particular rhythmic structure by controlling the metre of the poem.

With Matrix+ Online English Courses, you will have access to theory video lessons that teach you your English content step-by-step, extensive resources that are mailed to your doorstep, and Q&A boards with expert English teachers to answer your questions!

Learn more about Matrix+ Online Courses now.

Get ahead with Matrix+ Online

Expert teachers, detailed feedback and one-to-one help. Learn at your own pace, wherever you are.

In English poetry, there are a handful of common metre types that you may come across.

However, you can’t just refer to the metre to describe the poetry.

You have to refer to it as foot metre.

For example, Shakespeare’s favourite: iambic pentameter. Here, iambic is the foot – the type of rhythm and number of syllables in the foot, that is an iamb (da-DUM) – and pentameter – 10 syllables to a line – is the metre.

So, let’s examine the different types of feet and metre:

Feet are harder to remember than metres (you’ll see why in a second). So, write them down in your notes and continue to memorise them!

Remember in English language poetry, a foot is either 2 or 3 syllables long.

Here are the different types of feet:

It is very easy to identify the metre if you know your numerical prefixes!

Here are the different types of metre:

Note: Pay attention to the spelling – metre vs meter. Metre is the UK and Australian spelling. in the United States, they use meter.

A metre forms the rhythmic structure of a poem.

Poets can stick to 1 metre throughout the poem, switch between different metres or totally ignore metres.

These will create different rhythms which shapes the atmosphere and flow of the poem and subsequently, the reader’s emotions.

A good way to think about metre is the poet putting rhythms into your mouth to speak!

For example, TS Eliot follows iambic tetrameter for the majority of Preludes. This creates a sense of structure and flow.

Many times, students overlook metre in poetry because it’s too confusing or difficult to analyse. However, these steps will make analysing metre easy!

So, let’s see what each of these steps require you to do.

Note: In the next section, we go through these steps with an example from Rosemary Dobson’s Young Girl at a Window.

In the first reading, you must read the poem as a whole ALOUD without writing anything down.

Pay attention to:

This will help you better understand the poem as a whole and determine why the specific metre is used.

If you’re struggling to understand the poem, break it down into smaller parts:

Now that we have a feel of the poem, it is time to identify the poem’s metre. For longer poems like Eliot’s ” The Lovesong of J Alfred Prufrock”, this could take ages

To do this, you need to:

1. Pay attention to the rhythmic patterns.

Remember, we want to be efficient when we analyse metre. You don’t want to count every line in the poem.

So, get out a pen, and draw brackets around stanzas or set of lines with prominent/different rhythmic patterns. This includes any structured metres, irregular metres, stanzas that don’t follow metre etc.

2. Count the stressed & unstressed syllables to determine a metre

Once you’ve identified these stanzas/set of lines, start counting the number of feet in 1 line. Use your fingers to help you do this.

Remember, a foot usually refers to 2 syllables eg. da-DUM, but sometimes poets use a tri-syllabic metre like dactyls and anapests.

Then, start figuring the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in the line. You can put dots above stressed syllabus and underline unstressed syllables to help you figure this step.

Take note of your findings.

Note: Remember, you don’t need to do this for all the lines. Just select one line of each identified stanza/set of lines to save your time. However, if you feel the need to count more lines, then feel free to do so.

3. Identify any changes in metre throughout the poem

After you identified the metre for the stanzas/set of lines, you need to identify any metre shifts throughout the poem.

Does it change from a structured metre to an irregular one? Does the metre stay consistent throughout the poem?

Write down your findings.

When we determine the significance of metre, we figure out its effect on the readers.

This refers to the composer’s purpose and the audience reception. How does the metre help the poet convey meaning and how does the audience receive it?

We need to do this step for all your important stanzas and set of lines.

1. What is the subject being discussed? Refer to the poem’s themes.

You need to know what is happening in each important stanza/set of lines. Break down the lines to help you do this.

Then, figure out how the poem’s events link back to the themes.

2. How does the metre make you feel?

Remember, different rhythmic patterns will have a different effect on the reader. So, pay attention to how the rhythm makes you feel as you’re reading the stanza/set of lines.

Do you feel uncomfortable, free, anxious etc?

3. Link the two findings

Now, we need to find a link between the subject of the poem and your feelings to figure out the effect of the metre.

To help us do this, we need to ask ourselves:

Usually, poets will use metre to make you feel a certain way towards the subject being discussed. It is up to you to figure out why!

Now, we have all the necessary ingredients to put together a T.E.E.L paragraph.

T.E.E.L stands for:

You can find a more detailed explanation of using T.E.E.L in our post on paragraph structure (this post is part of our series on Essay Writing and shows you the methods Matrix English Students learn to write Band 6 essays in the Matrix Holiday and Term courses).

Let’s learn how to analyse metre with Rosemary Dobson’s Young Girl at a Window.

“Lift your hand to the window latch:

Sighing, turn and move away.

More than mortal swords are crossed

On thresholds at the end of day;

The fading air is stained with red

Since Time was killed and now lies dead.

Or Time was lost. But someone saw

Though nobody spoke and nobody will,

While in the clock against the wall

The guiltless minute hand is still:

The watchful room, the breathless light

Be hosts to you this final night.

Over the gently-turning hills

Travel a journey with your eyes

In forward footsteps, chance assault—

This way the map of living lies.

And this the journey you must go

Through grass and sheaves and, lastly, snow.”

What is the poem about?

Dobson explores the themes of adulthood, change and acceptance in this poem. The young girl is faced with an obstacle, which she learns to slowly accept throughout the poem.

How does the metre make you feel?

The metre feels very rigid, structured and constricting.

From our first reading, the metre of the poem already feels very structured and rigid.

However, we should still carefully examine the metre in each stanza to identify any changes.

So, let’s count the number of feet and the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables of a few lines of each stanza. Remember to select lines that have a strong rhythm.

Stanza 1:

Notice how the first line of the stanza doesn’t follow a particular feet pattern.

“Lift your hand to the window latch:”

However, when we look at the final 2 lines of the stanza…

“The fading air is stained with red

Since Time was killed and now lies dead.“

We see that both lines are made of 4 feet (tetrameter) and follow the iambic feet pattern (unstressed-stressed)

Therefore, we see that Dobson only follows iambic tetrameter for the final few lines of the stanza 1.

Stanza 2:

The first 2 lines of Stanza 2 doesn’t follow a particular metre pattern.

“Or Time was lost. But someone saw

Though nobody spoke and nobody will,”

However, let’s see if the final 2 lines follow the same metre as Stanza 1

“The watchful room, the breathless light

Be hosts to you this final night.”

Both lines are made of iambic feet (unstressed-stressed) and each line has 8 feet (tetrameter).

As such, we’re beginning to see a pattern; Dobson only uses iambic tetrametre in the final lines of the stanza.

Stanza 3:

Let’s test our theory. Here are the first 2 lines of Stanza 3:

“Over the gently-turning hills

Travel a journey with your eyes“

Similar to the other stanzas, the first 2 lines of Stanza 3 does not follow a particular metre pattern.

Now, let’s examine the last 2 lines of this stanza:

“And this the journey you must go

Through grass and sheaves and, lastly, snow.”

It is an iambic tetrameter like the previous stanzas.

Collate findings:

As such, we see that Young Girl At the Window has a very controlled and rigid structure. She has 6 lines in each stanza and always ends her last 2 lines in iambic tetrameter.

Now that we know the metre of Dobson’s poem, we need to analyse it. To do this, we must find the significance of the metre.

So, let’s answer these questions to figure it out.

1. What is the subject being discussed? Refer to the poem’s themes.

Stanza 1: The girl is approaching the end of a stage in her life. She is reluctant to accept this change.

Stanza 2: This stanza is more hopeful. The girl is now questioning her own perception and is opening up to the change.

Stanza 3: The girl accepts the change.

2. How does the metre make you feel?

As previously discussed, the structure of the whole feels very rigid and structured. This makes us feel like we’re stuck and we have limited freedom.

The fact that Dobson’s final couplets of each stanza follows an iambic tetrameter furthers this feeling of rigidity.

3. Link the two findings

The controlled and definite structure of the poem represents the rigidity of life. Individuals cannot simply reject changes in life because they will soon be stuck in the past.

This is especially represented through the symbolic use of metre. For every stanza, Dobson doesn’t follow a particular metre until the last 2 lines where she shifts to iambic tetrameter.

As such, the lack of a metrical pattern at the beginning of each stanza represents human’s attempts to challenge life and reject change. However, the fact that Dobson always returns to iambic tetrametre highlights how change is inevitable and the only options available is to embrace these changes or be left behind.

Therefore, her use of metre symbolises how changes in life is inevitable, regardless of the individual’s effort to challenge it.

Now that we have our technique and analysis, it is time to put it in a TEEL paragraph!

Remember, TEEL stands for:

Rosemary Dobson explores the need to embrace and accept changes in life. This is demonstrated through the controlled and structured metre of Young Girl At the Window. Dobson begins every stanza without following a particular metrical pattern. However, the final couplets of every stanza is always written in iambic tetrameter, for example, “The fading air is stained with red / Since Time was killed and now lies dead” and “The watchful room, the breathless light / Be hosts to you this final night”. This creates an uneasy atmosphere because it feels very rigid and provides limited space for change. As such, the metrical pattern is symbolic of the inevitability of change as Dobson always falls back on iambic tetrameter in every stanza, despite straying away in the beginning. Therefore, this confronts her audience with the need to embrace these changes or they cannot continue to progress in life. |

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.