Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Select a year to see available courses

Science guides to help you get ahead

Science guides to help you get ahead

Ever read a poem and thought, “What does that even mean?” This guide breaks it down with key poetry techniques and analysing poems examples made just for Year 7–8 students.

Join 75,893 students who already have a head start.

"*" indicates required fields

Related courses

Join 8000+ students each term who already have a head start on their school academic journey.

If you’re in Year 7 or Year 8, this blog will guide you through how poets use language, structure and style. By the end, you’ll be writing and analysing poetry in English class like a pro!

Table of contents:

Poetry is hard to define, but most people agree that poetry:

HSC writing strategies from expert English teachers

Band 6 resources to get you exam-ready. Join the 96% of our students that have improved their marks.

Authors use poetry to express ideas, emotions and perspectives. It helps us:

Whether you’re studying Shakespeare, poetry by First Nations people, or contemporary verse, poetry provides a deeper understanding of human experiences.

Curious about Shakespeare? Read our step-by-step guide on How to Analyse Shakespeare.

Poets do more than put words on a page: they shape how we see and feel. Here’s a look at some key poetic techniques and how they work.

Understanding these tools can help you unpack their deeper meanings when asked to analyse a poem.

The table below outlines the main types of poetry, including what they mean and popular examples of each.

| Term | Definition | Example |

| Sonnet | A 14-line poem, often about love or deep emotions | Shakespeare’s sonnets |

| Haiku | A short Japanese poem with three lines (5-7-5 syllables), focusing on nature and simplicity. | Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) and Fukuda Chiyo-ni (1703-1775) are just two famous haiku poets |

| Limerick | A five-line poem with the rhyme scheme aabba, usually to produce a humorous effect | A Book of Nonsense (1846) by Edward Lear |

| Spoken word | A performance-based poetry style, meant to be heard rather than read. | “Whitey on the Moon” (1970) by Gil Scott-Heron “A Bird Made of Birds” (2019) by Sarah Kay |

| Ballad | A narrative poem that tells a story, often with a rhythm and repeated refrains. | “It was not Death, for I stood up” by Emily Dickinson |

| Ghazal | An Arabic and Persian form made up of couplets and complex rhyme schemes. | Rumi’s ghazal 163 (approx. 1247) “Tonight” (2003) by Agha Shahid Ali |

| Free verse | A poem with no set structure, rhythm, or rhyme, allowing more creativity with rhythm, rhyme and meter. | Leaves of Grass (1855) by Walt Whitman “Tulips” (1962) by Sylvia Plath |

| Blank verse | A poem written in unrhymed iambic pentameter (structured but without rhyme) | Macbeth (1623) by Shakespeare |

Here’s an annotated extract of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Even though it’s from a play, it’s written in blank verse, a poetic form that Shakespeare often used for serious or reflective moments. It reads like a poem and uses rich figurative language to express Macbeth’s despair.

| Term | Definition | Example |

| Sound Devices | Used to create effects through sound, enhancing meaning and experience. | Onomatopoeia |

| Rhythm | The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of poetry, creating a beat. | Meter, stressed and unstressed syllables |

| Rhyme | The repetition of similar sounds, typically at the end of lines, to create musicality. | Fast, last, cast, mast |

| Meter | A structured pattern of rhythm in poetry, often measured in feet (units of stressed and unstressed syllables). | Iambic pentameter |

| Syllable | A single, unbroken sound unit within a word. | Cus|tard, oc|cu|pa|tion |

| Line | A single row of words in a poem, contributing to its rhythm and meaning. | “Me, we” (1975), a single-line poem by Muhammad Ali |

| Stanza | A grouped set of lines in a poem, often separated by spaces, functioning like a paragraph. | “Hope” is the thing with feathers – That perches in the soul – And sings the tune without the words – And never stops – at all – – Emily Dickinson, first stanza |

When creating poetry, a poet carefully chooses words to create an effective, whether to spark emotions or to create a vivid picture in your mind’s eye.

| Technique | Definition | Example | Famous poem |

| Metaphor | A direct comparison between two unrelated things | “Hope is the thing with feathers“ | Hope is the thing with feathers – Emily Dickinson |

| Simile | A comparison using “like” or “as” | “Like a patient etherised upon a table“ | The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock – T.S. Eliot |

| Personification | Giving human qualities to non-human things | “Because I could not stop for Death, he kindly stopped for me” | Because I Could Not Stop for Death – Emily Dickinson |

| Alliteration | Repetition of consonant sounds at the beginning of words | “Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary” | The Raven – Edgar Allan Poe |

| Onomatopoeia | Words that imitate sounds | “How they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle” | The Bells – Edgar Allan Poe |

| Imagery | Descriptive or figurative language that appeals to the senses, helping the reader visualise scenes, objects, or emotions. | “The fragrance of a fumy pipe; The smell of apples, newly ripe; And printer’s ink on leaden type.” | “Smells” by Christopher Morley |

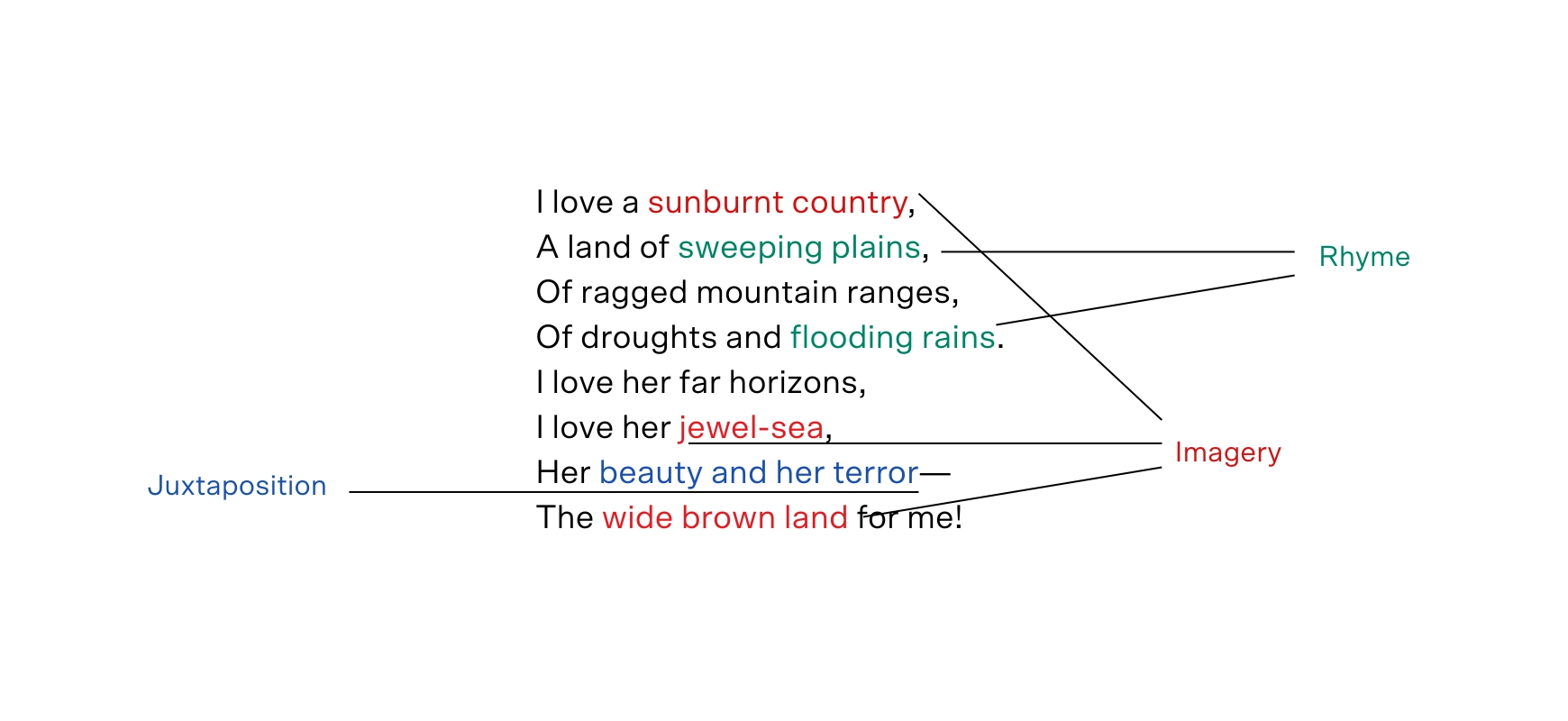

Here’s a short excerpt from Dorothea Mackellar’s My Country, annotated to highlight poetic techniques like rhyme, imagery, and juxtaposition (key things you should look for when analysing poetry).

This shows how these techniques work together to create emotion and meaning in poetry!

Check out our annotated Asian Australian Poetry essay, written for Module A and marked up by an HSC expert.

This exemplar shows:

Learn why HSC markers would score this essay highly

Fill out your details below to get this resource emailed to you.

"*" indicates required fields

When analysing a poem, ask yourself these key questions:

Below is a model response analysing Wildred Owen’s war poem “Dulce et Decorum Est”:

| Paragraph | Part | Example |

| Introduction | Thesis | Owen’s war poem “Dulce et Decorum Est” represents the horrors and trauma of war from the first-person perspective of the persona, a soldier who directly experiences warfare. |

| Explanation | Owen shows how the soldier observes the horrors of war first-hand, then reflects on his experience and shows how he feels haunted by these horrifying memories. | |

| PEEL (Body) | Topic | Owen’s war poem “Dulce et Decorum Est” represents the first-person perspective of a soldier. The persona observes his comrades, a group of tired and wounded British soldiers on the battlefield, as they try to escape enemy attacks of flares and gas bombs. |

| Explanation | Owen represents the horrors of war by using sensory imagery that immerses the reader and lets them experience the “gas-shells dropping” and the “haunting flares.” | |

| Evidence (Use 2-4)

| Owen uses the simile comparing the tired soldiers to “old beggars under sacks” to emphasise their exhaustion and show how difficult life on the battlefield is. Owen appeals to pathos by awakening the reader’s emotions of pity, compassion and sympathy for the soldiers as they experience the exhausting effects of warfare. | |

| Evidence

| When a gas bomb explodes and the soldier fails to put on his gas mask in time, Owen uses a metaphor of the soldier “drowning” “as under a green sea” to show how this soldier experiences a horrible death. | |

| Evidence

| He uses violent imagery when the persona describes how the soldier “plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning” to highlight the gruesome effects of the gas on the soldier. | |

| Evidence | Owen represents the persona appealing to the reader as “my friends”: He argues that if they were to take the perspective of a soldier who experiences the horrors of war first-hand, then they would not glorify war. And they would not repeat the lie of the motto “dulce et decorum est/ pro patria mori” (it is sweet and right to die for your country). | |

| Link | Owen creates a horrifying and disturbing representation of war from the perspective of a soldier to warn people against having an idealised and glorified representation of war. |

Put your skills to the test: Try analysing “Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley. What themes and poetic devices can you identify?

Imaginative writing, including poems and other fiction texts, is a key skill in high school English. Even when you’re not asked to write a poem, you can still use the techniques of poetry to create expressive language!

Now that you know how poetry works, why not try writing your own? Here’s how:

Try this exercise: Write a poem about a place you love, using at least one metaphor and one sensory image.

Poetry can be tricky at first, but with the right tools, it becomes much easier to understand and write about. By learning to spot key techniques like structure, language features, and figurative devices, you can build real confidence in English.

If you want to learn with the experts, enrolling in a Matrix English course can help!

Written by Matrix Education

Matrix is Sydney's No.1 High School Tuition provider. Come read our blog regularly for study hacks, subject breakdowns, and all the other academic insights you need.© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.