HSC Physics Trial Exam Preparation Course

The HSC Physics revision course will help you revise and get exam ready in a week.

Learning methods available

Select a year to see available courses

Practical assessments are designed to test your practical skills: how well you can design and carry out an experiment and analyse results, but also your understanding of the purpose of the experiment and its limitations. One aspect of this is the reliability, validity, and accuracy of the experiment. So what do these terms mean and how do these things affect each other?

Learn how to:

with the Matrix Practical Skills Workbook.

An experiment is a set of measurements that are analysed to test a link or relationship between different things. The measurements are usually analysed in an experimental report, which is set out in a clear format to help the reader understand different aspects of the experiment, like the aim, the equipment and method used, the results obtained, how they were analysed, and what conclusions can be drawn.

When writing the method of an experiment, you must ensure that each step of the method incorporates reliability, accuracy or validity.

Validity relates to the experimental method and how appropriate it is in addressing the aim of the experiment:

Several aspects of the experiment can contribute to validity: the equipment, the experimental method, and the analysis of the results.

Although it may seem obvious, the appropriate equipment needs to be used. The equipment must be suitable for carrying out the experiment and taking the necessary measurements.

The experiment is ultimately testing a relationship between cause and effect: how changing X affects Y. To address this, you must only change X, and see what happens to Y. If you allow other changes at the same time, then you cannot make a valid conclusion about how X affected Y, since Y may have been affected by the other changes as well.

The correct way to describe this is in terms of the independent, dependent, and control variables. The independent variable in an experiment is the one you set (X). The dependent variable is the one you measure (Y, because it depends on X). All other variables are called control variables, and they must be kept constant to prevent them from affecting the dependent variable. This forms part of the experimental method.

The method (including the analysis) may contain some assumptions that need to be satisfied, e.g. maybe something has been simplified, or an equation being used is an approximation. The experimental method must ensure that all the assumptions are satisfied, otherwise, you will end up using a method or analysis that is inappropriate, and the result will be invalid. You may be able to identify invalid measurements and discard them from the analysis.

If your experiment is invalid, then the result is meaningless because either the equipment, method or analysis were not appropriate for addressing the aim.

An example from Module 6 Electromagnetism, is an experiment involving transformers, using the transformer equation: \(\frac{N_p}{N_s} = \frac{Vp}{Vs} \).

Physics doesn't need to be confusing

Expert teachers, detailed feedback, one-to-one help! Learn from home with Matrix+ Online Courses.

Reliability is about how close repeated measurements are to each other. You can consider the reliability of a measurement, or of the entire experiment.

A measurement is reliable if you repeat it and get the same or a similar answer over and over again, and an experiment is reliable if it gives the same result when you repeat the entire experiment.

You can test reliability through repetition. The more similar repeated measurements are, the more reliable the results. However, repetition alone doesn’t make your measurements reliable, it just allows you to check whether or not they are reliable.

Improving reliability is a different matter to testing it. The reliability of single measurements is not improved through repetition, but through the design of the experiment. Implementing a method that reduces random errors will improve reliability. However, the entire result of the experiment can be improved through repetition and analysis, as this may reduce the effect of random errors.

The table below provides a summary of reliability.

| Reliability of single measurements | Reliability of entire experiment’s final result | |

| Definition | Repeating single measurements gives the same values. | Repeating the entire experiment gives the same final result. |

| How to improve | Through experimental method, e.g. fix control variables, choice of equipment. | Improve the reliability of single measurements and/or increase the number of repetitions of each measurement and use averaging e.g. line of best fit. |

| How to test | Repeat single measurements and look at difference in values. | Repeat entire experiment and look at difference in final results. |

To learn more about random errors, read Physics Skills Guide Part 3: Systematic vs Random Errors.

Reliability can be affected by the validity of the experiment.

If an experiment is invalid because of an inappropriate method being used, the result may still be reliable, it just won’t address the aim of the experiment.

However, if an experiment is invalid because the control variables are not constant, then they may be affecting measurements in an unpredictable way, making the result unreliable.

Accuracy is much easier to define: the accuracy of an experiment is how close the final result is to the correct or accepted value. The closer it is, the more accurate the experiment.

The accuracy can be improved through the experimental method if each single measurement is made more accurate, e.g. through the choice of equipment. Implementing a method that reduces systematic errors will improve accuracy.

Note that, precision is a separate aspect which is not directly related to accuracy. Precision refers to the maximum resolution or the number of significant figures in a measurement. For example, a clock has a precision of 1 s, whereas a stopwatch has a precision of 0.01 s. Whether or not a measurement is accurate does not depend on the precision.

You can test the accuracy of your results by:

The table below provides a summary of accuracy.

| Accuracy of single measurement | Accuracy of entire experiment’s result | |

| Definition | How close the measurement is to the value expected from theory. | How close the final experimental result is to the accepted value. |

| How to improve | Reduce systematic error by calibrating equipment. | Improve accuracy of individual measurements. |

| How to test | Compare measurement to value expected from theory. | Compare final experimental result to accepted value. |

To learn more about systematic errors, read Physics Skills Guide Part 3: Systematic vs Random Errors.

Reliability and accuracy are separate aspects of an experiment and the relationship between them is sometimes misunderstood.

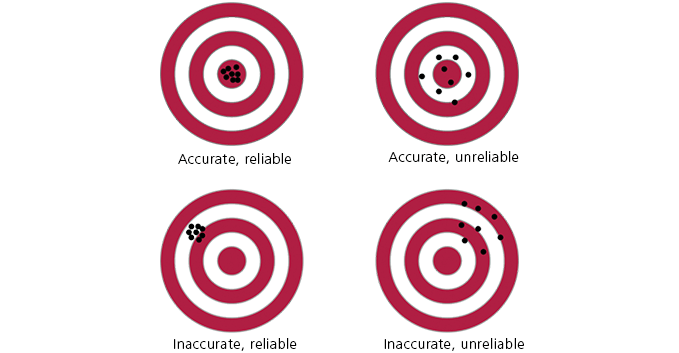

Consider the following table:

| Reliable | Unreliable | |

| Accurate | The correct answer all the time. | The correct answer on average, but answers vary between repetitions. |

| Inaccurate | The same incorrect answer all the time. | An incorrect answer overall, and answers vary between repetitions. |

A result can be reliable and inaccurate if you get the same incorrect answer all the time (e.g. your friend is always 10 minutes late), and it can also be accurate and unreliable (e.g. your friend is more or less on time, but sometimes early, sometimes late).

A result can be reliable and inaccurate.

We can use shooting at a target as an example to further clarify our understanding of reliability and accuracy:

In summary, all combinations are possible:

Some steps can be taken to improve both accuracy and reliability. For example, if you use better quality equipment, your measurements can be more reliable and more accurate.

If the measurement is easier to do, then you’re more likely to get the same result in each repetition.

Considering, for example, an experiment in which you must measure a short time period (around 1-2 s).

Ultimately though, you cannot make general conclusions about the reliability from the accuracy and vice versa. The reason is that they are affected by different types of experimental errors as mentioned above:

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.